The Sun empire

Son-nu-ha (Land of the Sun,

The Sun empire)

Government: Feudal authoritarian with protectorates

Head of state: Emperor Kenju-ka

Capital: Yun-Tian-Cheng

Ruling race: Ailvu

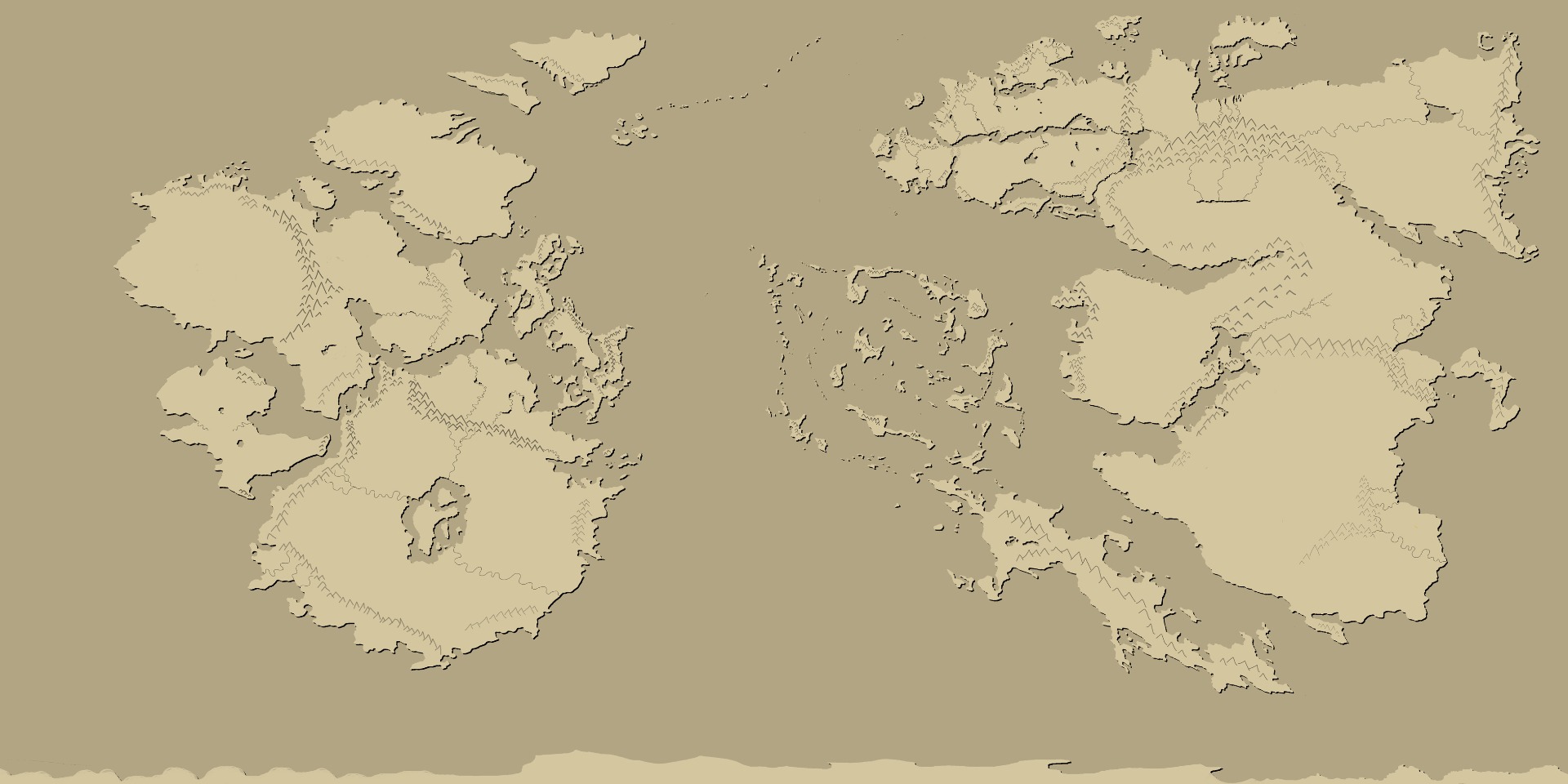

Son-nu-ha as an empire is made up of several protectorate states that cover the whole continent of the green land but are defined by imperial bureaucracy as prefectures. The empire has a strict hierarchy of power divided downwards from the emperor, which is seen as and believed to be the divine incarnation of Yun-ku-mo, the god of the sun and the sky, which is the highest deity of the empires religious faith. This is enforced by a cultural foundation of honor and a view that every action or decision is a reflection of a person's soul, meaning that honorable people make good deeds and choices while someone of low honor make bad decisions.

The empire saw its founding in the early era of strife, shortly after the war of the sages ended, as a way to unite all Ailvu. While at first there was good order among the people it soon fell into conflict and over a span of three centuries two large scale civil wars would be fought before a true unification would take place and an institution of imperial order. However this order is fragile and held in place by a strict hierarchical rules and an iron fist of bureaucracy.

Each prefecture is ruled by a noble chosen by the emperor and he only answers to the emperor, but has no power over other nobles (at least in an official stance). Being that each prefecture is essentially a protectorate, they more often than not have their own production of goods and sustainability, and are expected to pay an imperial tithe to the emperor. The tithe is expected to be part produce or material, and part currency. Should it be that the prefecture fails to pay the tithe, the noble that governs is blamed for its failure and his fate is decided by the emperor. Besides any punishment, the dishonor of failing ones task is a major stain on the individual and it's not uncommon for nobles that fall from grace in this way to perform a ritual suicide to redeem himself and his family.

As a strict hierarchy, each subject is obligated to know its place in the greater society and be humble to those above, as it is believed that each one carries the whole through their given task. However there are some questions of interpretation on the meaning of this. A common argument is that even the lowliest peasant needs to be given the same respect as the high noble by demand of honor for their task to uphold society. The reality however is that nobles rule over their subjects with impunity, some even being downright evil in their ways.

Nobles, being given their power from the emperor are rulers and lawmakers in their own domains. They are expected to bring fortune and wisdom to their regions as well as provide any needed goods or favor that the emperor asks of them. Beneath the nobles are the bureaucrats whose task is to make sure that the orders and expectations of the ruling noble is fulfilled. Bureaucrats are really only administrators and record keepers but answer directly to the nobles. The title gives them a good income as well as the privilege of being able to order those of lower rank. Many times though a bureaucrat is an unnecessary cog in society that reaps the fruit of his rank but leaves all work to an assistant below him. It is not a position without danger though as any failure to fulfill the orders or demands of his noble could become his end, at best only losing his title but at worst being executed for the dishonor of failure.

Next in rank is the artisan, these master craftsmen also govern the guilds of their trade in their home prefecture, overseeing the work in the prefecture. The artisans are expected to guarantee that all crafting is done right and that production demands are met. Next in the hierarchy come journeymen and traders. Journeymen perform the work of whatever guild he is part of, taking orders from and being supervised by an artisan. Journeymen are expected to be proficient and effective in their trade and to take on apprentices to make sure that there always will be trained workers. The traders are those that deal with providing goods or services to all people in their area. Most traders only do local business, such as having a small store, run an inn or cookery, or as a peddler. Then there are the traveling sort that go between prefectures or with the right sanction to foreign lands. To become a trader, one needs the blessing of the ruling noble. For the local traders this is handled by any appointed bureaucrat. But for those that want to move between prefectures or do foreign trades, this requires a direct approval of a ruling noble and is more often than not done with bribes or favors given to the noble.

Lastly, there are the peasants, who in reality are serfs to a noble family and work the land to provide the prefecture with food and raw materials. The peasant isn't necessarily looked down upon by those higher in the hierarchy, but few treat them on any form of equal footing, especially nobles. As serfs they are supposed to be cared for by their ruling noble family, practically however, serfs are expected to care for themselves while also performing their tasks. This many times leads to miserable conditions for the serfs that work long days for their noble lords and rarely having enough time to provide for their own needs. There are a few that have managed to move above serfdom either through generation of hard work or by gaining a favor from a noble. These few are instead imposed with heavy tithes for the right to farm, which often leads to either going back into serfdom or becoming a soldier. This doubles as a means to make sure that free peasants don't rise above their station and that the most resources are provided to the state.

There is a group which is somewhat outside of the hierarchy, namely soldiers. There are few professional soldiers in the empire and most ranks are filled with levies, often drawn from the peasant. Being a soldier is not something that necessarily brings one honor or standing, but it does have benefits- like a regular salary and guaranteed quarters (as long as no campaign is ongoing). Each prefecture has its own military force, which is commanded by the ruling noble. This has historically led to nobles clashing with each other, using the resources within their prefecture to wage personal wars. Even though it's not forbidden, it is frowned upon and depending on the whim of the ruling emperor, these wars among the nobles may be allowed to go on until either side gives up or is fully defeated. Losing a war like this is often a death sentence for a ruling noble and his family, since they will be executed by the conquering noble for treason against the emperor (whether or not this is true matter little as it is literally the winner that writes the history).

The empire has been closed off from the rest of the world due to a practice of isolationism in a belief of preserving internal peace. However this isolation is done mainly for two reasons, one being to keep those in the lower under control, the other being a belief that other races and cultures are inferior and should be kept away. While no foreigners are officially allowed to set foot in the empire it is not uncommon for sanctioned merchants to be allowed to go abroad to procure goods for the nobles, be it exotic goods, spices, or even slaves.

In the last decades however, attempts have been made to officially open up to the outside world due to the realization of the technological inferiority of Son-nu-ha compared to the great empires of Evperia. As such attempts are made to establish diplomatic connections with the rest of the world. These efforts have been somewhat thwarted by nobles who instead believe that the only contact should be for conquering and subjugation. This is seen by some as a direct defiance against the emperor and thus the heavens, something that fans the flames of civil unrest.

Another effect of the long isolation and long time of strict hierarchy has resulted in a homogeneous but divided society taking the form of two extreme expressions of a high and a low culture. The high culture, practiced by nobility and high ranking bureaucrats expresses itself in a light and airy form where ceremony becomes the central point whereas the low culture takes on a heavy and robust form with expression focusing on sculptures and imagery. One could easily believe that expressions of art and beauty of these two stand right opposite from one another, but that is only true on a surface level. It would be more appropriate to say they are in a symbiosis of sorts since they over time take inspiration from each other where one will create a style inspired by the its opposite for it to later become an inspiration for the other. There are however aspects that are more cemented in each separate culture, such as how the high culture see beauty and value in fragility and overabundance while the low culture see the same in strength and temperance.

These views of beauty are also reflected on the individual. For the high culture a frail body with pale skin and grey eyes is the highest form of beauty, while the low culture idealize a trimmed and hard body with olive skin and amber eyes. But despite this there is much variation among both cultures which makes those that embody the ideal image a bit exceptional. Further each culture has preference in style of clothing. The high culture prefers clothing made with materials that are light and flimsy, and dress in multiple layers. The low culture on the other hand uses materials that are strong and durable for at the most two layers of clothing.

Ailvu of Son-nu-ha values a clean and unblemished body, especially those of the upper ranks of the high culture. Blemishes and permanent marks, such as scars or tattoos are seen as imperfections or marks of failure. Scars, while not truly accepted, can be tolerated. Broadly it is seen as a sign of a lack in skill. A soldier with a scar is seen to being or having been poor in his trade, otherwise he would not have a scar. A commander with a scar is either reckless or poor in judgment to have been in battle at all. A carpenter with scars is seen as clumsy or lacking precision. The only one that is not shamed not looked less upon for having scars are farmers, mostly since there is little respect for them to begin with. Among some in the higher ranks, there is an expectation that a farmer will bear scars since if they had any skill they would be anything but a farmer.

In Son-nu-ha tattoos are especially despised. The reason for this contempt is the combination of permanency and it being unnatural to the body, in contrast to a scar which at least comes as a result of natural healing. Tattoos are therefore used to mark criminals and slaves. The tattoo is places either on the face, neck, hands or other part where it is easily spotted and hard to conceal. The shape of the tattoo for criminals is all the same no matter the crime. However not all forms of crime will result in being tattooed. Single instances of small crime, such as petty theft, begging, drunken rambling, or assault of someone of equal rank, will instead be punished by lashings and a forced public bow for forgiveness. Multiple instances of this sort or a more major crime like burglary, mugging or assault of a person of higher rank except a noble, will result in a criminals tattoo along with other punishment. High crime, such as murder, massive property damage, or assault of a noble, will end in execution.

Technologically, since being isolationists, Son-nu-ha lacks the same level of knowledge as the other empires, only recently learning about steam engines and the wonders of trinitum. They do however have great knowledge of carpentry and certain metalworking, making their artisans among the best in the world when it comes to handcrafted items. Though somewhat lacking in exact precision as they don't work within principles of standardization, an individual crafted piece may still rival that of the outside world. As long as it works, that is.

A longstanding view among the ailvu of Son-nu-ha is that something long or tall is a sign of luck and prosperity, and the opposite is a sign of weakness and misfortune. Because of this, they use this as a sort of marker in everyday life to judge or foretell someone's fortune. Things such as a long life mean that a person is wise and blessed, and should therefore be respected and obeyed, or if someone is tall, it means they are blessed with fortune and meant for great things, making people want to use them to draw in fortune to themselves. Likewise if something is short it is a sign of warning, bad luck or outright misfortune. If someone would die young it was because the lack of years did not guard against misfortune, or if someone is short they are marked by misfortune and bring it wherever they go.

This view has lead to many peculiar events and

misconceptions. One good example is the somewhat strained relation with the

dworig, whose short stature embodies the ailvus idea of misfortune, adding on

to this is the stout and broad features that ailvu view as downright ugly. It

has also affected the view on humans which usually are taller than ailvu and as

such is seen as blessed by fortune. However, an ad-hoc was added at some point

that being tall alone was not enough to be blessed for fortune, one also needed

to have long ears for it to be realized, meaning that humans aren't really

truly blessed. The effects of these views have been detrimental to relations

between Son-nu-ha and other races, especially the dworig that almost inevitably

will be mocked, scorned or shunned because of their features and the belief

that they bring misfortune. Relations with humans and uruk are better in

comparison as both are taller than ailvu, which up until the added rule for

long ears, were seen as being a sly way to bring some fortune by having

relations. Still, for an ailvu, humans are always preferable to uruk since

humans are at least somewhat alike the ailvu in appearance but removed enough

that they appear weird. The uruk on the other hand are just tolerated and their

features are seen as ugly.